Cornell University. Texas A&M. The University of California. Some of the top American universities and university systems share a common identifier: They’re land-grant colleges, created in the mid-19th century after the passage of the Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862.

The country’s 100-plus land-grant colleges — which include large state universities and even some private schools — are among its most beloved bastions of higher education. But according to Margaret Nash, a professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Riverside, their positive reputation belies a history that has gone mostly unrecognized.

Nash is a historian of education whose previous research examined the experiences of women and LGBT populations in higher education. In recent years, she’s shifted her focus to land-grant colleges, which she describes as elements of settler colonialism and agents of American Indian dispossession.

The Morrill Acts, along with the Homestead Act, railroad land grants, and the Hatch Act of 1887, were part of a suite of legislation that encouraged western settlement in the latter half of the 19th century. Beginning in 1862, the first Morrill Act made more than 10 million acres of so-called “public” lands available to be sold, with their profits “donated” by the federal government to the establishment of public colleges and universities geared toward agriculture and applied sciences.

“Their very name — land-grant colleges — assumes that there was just land available,” Nash said. But in fact, quite the opposite was true; the land for sale, mostly west of the Mississippi River, was inhabited by various tribes that were displaced.

Who granted the land?

Nash explores the effects of the act and development of land-grant universities in an article, “Entangled Pasts: Land-Grant Colleges and American Indian Dispossession,” published this week in the History of Education Quarterly.

“The article addresses two strong links between land-grant colleges and Indian dispossession,” she wrote. “The first is that some of those colleges were built on land that had been occupied by American Indians prior to the act; these land-grant colleges were founded on appropriated land, and the history of that land is relatively easy to trace.”

The second link, though, is harder to trace. All land-grant colleges were funded by the sale of formerly Native land, Nash said. But since most states east of the Mississippi River had no “public” land left to sell when the first Morrill Act was passed, those states instead were given certificates of “scrip,” which granted them profits from the sale of western land to fund the colleges in their states.

“Buyers bid on the scrip,” Nash wrote. “Those buyers could be individuals looking to move west, or land companies or individuals who bought large tracts of land to resell. Most states sold their shares to brokers, who sometimes acquired huge quantities.”

Thus, a land-grant college in an eastern state — one example is New York, which received scrip for nearly 1 million acres — could’ve easily been funded by the sale of western land hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

Nash noted that in some western states, such as Nebraska, tribes had often been forced to cede their land and relocate to federal reservations decades before the passage of the first Morrill Act.

The University of Nebraska, for instance, was founded in 1869 and built on land formerly occupied by the Otoe and Missouria tribes, which relinquished their remaining property after Congress formally opened the area to white settlement in 1854. The Otoe-Missouria people now live together as one tribe in Oklahoma, where their population hovers around 1,500.

Nash also used Bureau of Land Management records to track the sales of western land and decipher which eastern states’ colleges benefited from those sales. She focused her research on two states: Arkansas and Missouri.

Scrip sales of Arkansas land ultimately benefited land-grant colleges in Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Mississippi, Virginia, and West Virginia, she found. Scrip sales of Missouri land, meanwhile, benefited land-grant colleges in 19 eastern states, most notably West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maine, Ohio, and Kentucky.

“Educational institutions benefited, and, as a result, higher education was more easily available and more affordable to more people than ever before,” Nash wrote. “But the founding of the land-grant institutions came at a great cost.”

Those costs were acutely felt by tribes such as the Quapaw, whose displacement from their land in Arkansas benefited the University of Delaware, among other institutions, she explained.

A path forward

Nash said she was inspired to research land-grant universities after reading Craig Steven Wilder’s 2013 book, “Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities,” in which the author investigates the role of slavery in development of the elite schools of the colonial era and early years of the republic.

“Wilder says racism was part of the foundation of the colonial and early republic colleges, whereas many earlier historians had said, ‘Sure, there was racism, but that wasn’t the point; the point was to educate and uplift,’” Nash said. “Some historians have said the same about land-grant colleges, too — that even if there was racism involved, it wasn’t the point of them. But how could it not be? The land-grant colleges could not have existed without the racism that saw Native Americans as ‘other’ and not worthy of full consideration so that their land could be taken.”

As pushes for reparations for the descendants of enslaved people become stronger, Nash hopes land-grant colleges similarly make strides toward recognizing their histories.

“Acknowledgement is a good first step, and can help inform responsible citizenship,” she said. “It’s important to recognize that there are repercussions to things that happened in the past, and that those repercussions don’t just go away after a generation or two has passed. There are often long-lasting implications.”

For starters, colleges might consider adopting land acknowledgment statements that recognize the indigenous peoples who once occupied their land but were forcibly removed, as well as the colleges’ responsibilities toward making that history known today, she said. They might also work to develop closer ties with tribal communities, provide on-campus support for Native students, and make a commitment to teaching Native history.

Overall, Nash said she hopes her research will help people be aware of the past and the impacts of their decisions.

“We need to be conscious that our decisions do have long-lasting effects,” she added. “How can we make good decisions in the present if we live in a world where none of the decisions of the past have any repercussions?”

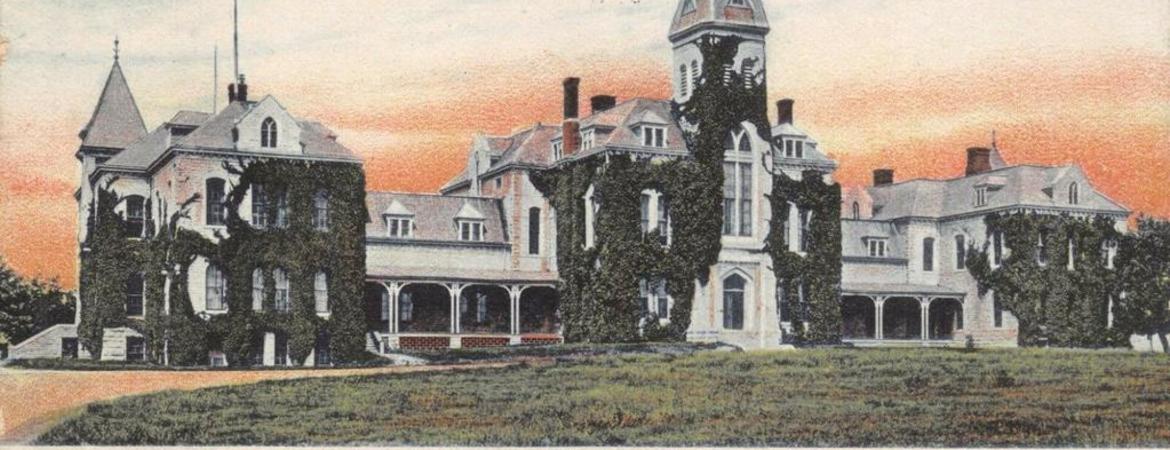

Header image: Pictured in a vintage postcard, Kansas State Agricultural College, now known as Kansas State University, was founded in 1863 as the nation's first operational land-grant university.

This piece was originally published in UCR News.